AfterJoyce (Part 2)

Nationalism and what newspapers have to do with Ulysses (and what TikTok might).

As I was wrapping up my class on James Joyce this semester, I held an informal final class session just to shoot the breeze with my students about Joyce and their experiences reading his work. It was a great chat and a fun end to an amazing course.

Somewhere in that conversation we found ourselves discussing what a modern Ulysses might look like. It’s a funny question, in a way, since Ulysses is already a modern retelling of an ancient story. But the point stood: what would a 2024 Ulysses look like, just over a century after it was published? My students had some interesting insights, but I spat out a textbook curmudgeonly spiel about how half the book would be about what Leopold Bloom or Stephen Dedalus was looking at on their smartphone. I argued that our internet and our technology would only muddy Joyce’s vision, and it wouldn’t be as good a creative project.

Shortly after that final class, my dad sent me a link to this essay in The New Yorker, which made me rethink everything I had said in class just the other day. (I also emailed my students a truncated version of this essay as a formal redaction.)

I won’t get overly into what the New Yorker article is about, but basically it’s concerned with media and provocation. In the article, Joshua Rothman thinks about how to live in a world full of provocation, full of incessant information flooding our day-to-day—or minute-to-minute—lived experience. It's about our deeply media-mediated world, and about the smartphones most of us carry with us and sometimes compulsively gaze into. (I think here of the TikTok skit where a guy walks up to a smoker and asks to "bum one," meaning could he spend a few moments scrolling TikTok on the guy's phone for a little dopamine hit.)

Again, I don’t mean to overly go on about what Rothman says in his article, except to point out that he, quite curiously, ends by invoking James Joyce:

"In Ulysses, James Joyce imagines Leopold Bloom strolling around Dublin. Bloom looks idly at passersby and wonders about them; he’s prompted by the contents of the newspaper into memories and reveries; he wanders into a drugstore and fantasizes about the exotic lands in which the toiletries are made. It’s 1904, and there’s not a screen in sight. And yet Bloom’s quaint, daydreamy reactions are prompted by what, in Joyce’s time, was understood to be a new and overwhelming urban modernity, a kind of attentional bombardment."

Here, Rothman's appeal to Joyce is right, and it shows where I was wrong. It's not that Ulysses couldn't be written today because of our phones and the internet—I realize now that to say that was as shortsighted as saying Joyce couldn't have written Ulysses because of the technology of the newspaper. For one, he did; but moreover, it was precisely the relatively new-fangled media technology of the newspaper that allowed for Joyce’s poignant insights into the experience of modernity. Scholars have long said that Ulysses is a novel of the newspaper. I don’t just mean that newspapers feature largely in the book (though they do), but that the very design is only made possible by the newspaper as a cultural phenomenon.

What I mean is that the newspaper is an ideological model for how to think about the novel, especially a strongly geographically situated novel like Ulysses concerned with the history, current state, and future promise of the nation. The way we come to think about the nation relies on how we view novels and newspapers alike, so the concepts are highly linked at the social and ideological levels. In Chapter 10 ("Wandering Rocks") of Ulysses, Joyce provides a kind of bird’s eye view of Dublin as we pop in and out of people’s movements around town. The chapter is comprised of short vignettes that each follow one person, but they’re also almost all cut with what Joyce scholars call “interpolations.” These interpolations cut quickly away from the subject of the current vignette to show, sometimes in just one sentence, what another is doing at the same time. Here’s an example:

“Corny Kelleher closed his long daybook and glanced with his drooping eye at a pine coffinlid sentried in a corner. He pulled himself erect, went to it and, spinning it on its axle, viewed its shape and brass furnishings. Chewing his blade of hay he laid the coffinlid by and came to the doorway. There he tilted his hatbrim to give shade to his eyes and leaned against the doorcase, looking idly out.

Father John Conmee stepped into the Dollymount tram on Newcomen bridge.

Corny Kelleher locked his largefooted boots and gazed, his hat downtilted, chewing his blade of hay.”

Kelleher is focus of this vignette, but Joyce “interpolates” Father Conmee in the midst of Kelleher’s feature to show Conmee’s simultaneous movement. These events are happening in different parts of the city, but Joyce allows the reader to see them all at once. It’s an important element of the novel as a form altogether, this notion of a “meanwhile,” which stems from our association with omniscient narrators. There’s a lot to say of this unique literary feature and its ideological results, but one scholar in particular I think captures it best.

In our class, I talked with my students about how this kind of simultaneity of disparate events recalls Benedict Anderson’s theory of an “imagined community.” In his book, Imagined Communities, Anderson is concerned with how nationalism developed in the modern age. The question is not how nations form as sovereign political institutions, but how we come to feel we are a nation. Of course, cultivating nationalism is an important part of maintaining the nation as a political body, but Anderson’s question is about the creation of a sense of belonging to a nation. What, for instance, makes me feel like I belong to the same nation as somebody living in California? To answer this, Anderson turns to the novel and the newspaper. What’s unique about the newspaper technology is the way it casts upon a single face of paper disparate events from around the world. Seemingly unrelated events are paired together in a kind of coherent logic. What’s important about it from an ideological standpoint is the date. Without the date to bind it together, the placing of events in coordination with one another on paper is meaningless; the meaning comes from their one shared feature: when they happened.

The novel and newspaper actually allow us to apprehend time in new ways, which then opens a path towards thinking about ourselves as part of a nation. Both novel and newspaper teach us how to think of the “meanwhile”—that temporal phenomenon of simultaneity of that which we cannot see but can imagine is occurring. Anderson distinguishes between what he calls the ancient and mediaeval apprehensions of time as opposed to our modern ones. Before the modern, apprehensions of time relied on “a simultaneity of past and future in an instantaneous present.” In this worldview, he continues, “the word ‘meanwhile’ cannot be of real significance.” Our modern version of simultaneity isn’t measured in this kind of “Messianic” time, but instead as “‘homogenous, empty time,’ in which simultaneity is, as it were, transverse, cross-time, marked not by prefiguring and fulfillment, but by temporal coincidence, and measured by clock and calendar.”

He continues by emphasizing the significance of the newspaper to this idea. Seemingly unrelated events are suddenly connected by arbitrary inclusion in the newspaper’s textual display. “The arbitrariness of their inclusion and juxtaposition,” Anderson says, “shows the linkage between them is imagined”:

“This imagined linkage derives from two obliquely related sources. The first is simply calendrical coincidence. The date at the top of the newspaper, the single most important emblem on it, provides the essential connection—the steady onward clocking of homogeneous, empty time. Within that time, ‘the world’ ambles sturdily ahead.”

As it turns out, newspapers and specific dates happen to be two things that are very important to Ulysses. Leopold Bloom is an advertisement canvasser for newspapers; he carries a newspaper that becomes deeply symbolic of his Homeric sword (among other things); and he encounters newspaper articles, advertisements, and other print media repeatedly (read: relentlessly) throughout the day. That day, of course, is June 16, 1904. If you didn’t know, Ulysses takes place over the course of one day, and the singularity of that day is one of the most important features of the book—and, I would argue, of its newspaper motif.

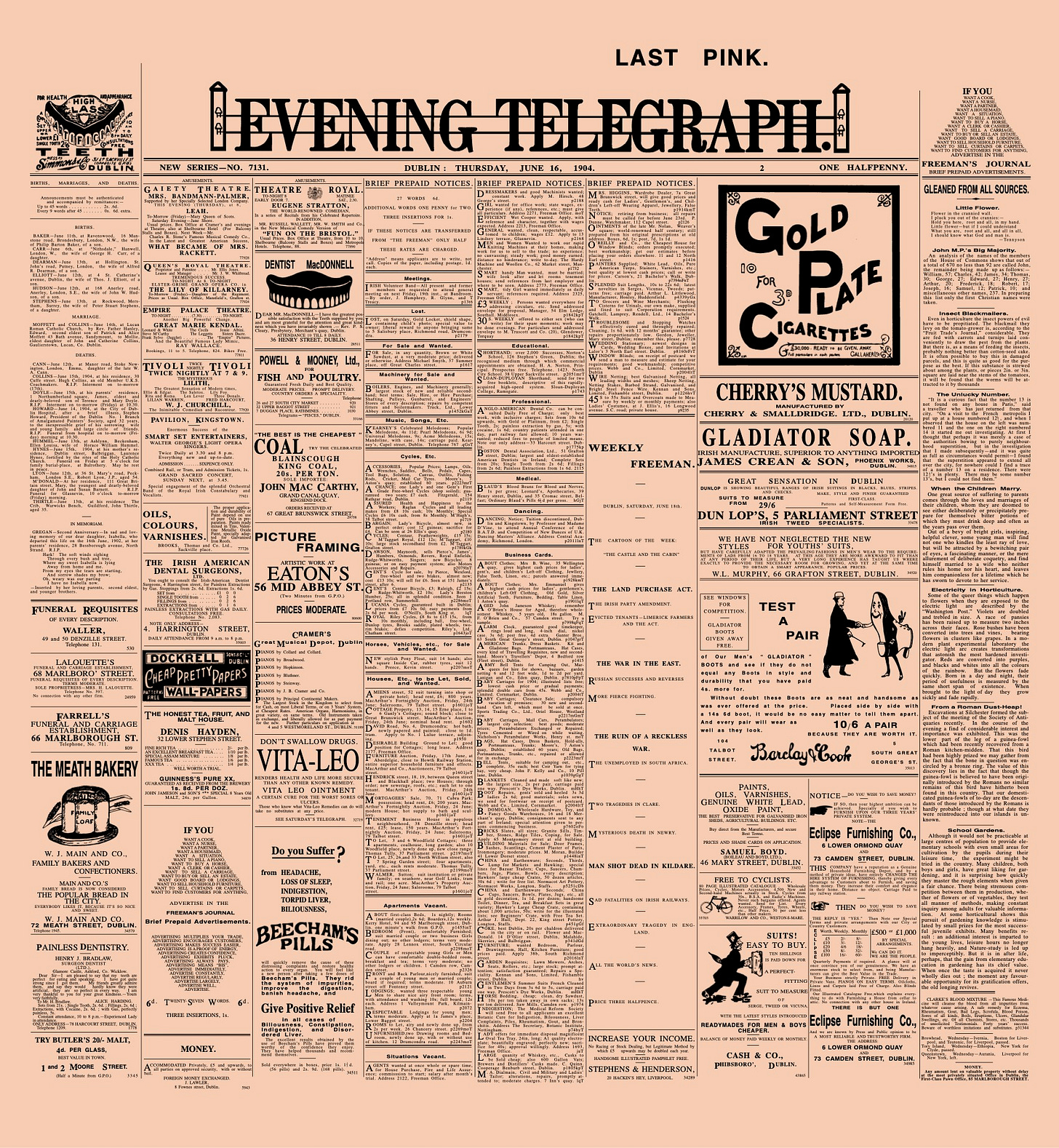

In our class, we examined a facsimile of the Evening Telegraph from June 16 1904, one of the newspapers Bloom reads in Ulysses. It was a fun exercise, especially since Joyce pulled so many of his plot elements from real newspapers, including that very edition of the Evening Telegraph. So, in this exercise, students were able to locate in the facsimile different historical events that made their way into the book. There’s a story about the Gaelic League and a ban on Irish sports, one on the Russo-Japanese war, another on a Canadian emigration scam, and one on the General Slocum disaster in New York City. These global stories all appear in passing references in Ulysses just as they appear simultaneously on the pages of the Evening Telegraph. Their simultaneity is what links them in our imagination and understanding. Like the stories in the newspaper, the figures we follow in “Wandering Rocks” and throughout Ulysses more broadly are linked in numerous ways, but first and foremost by their simultaneous existence—their complete coincidence of birth and temporal happenstance—in Dublin.

What Joyce saw on the pages of newspapers he aimed to rehearse in Ulysses, a kind of simultaneity of experiences coexisting at once. He did this best in the “Wandering Rocks” episode, where those nineteen vignettes explore the simultaneous movement of at least as many characters. The effect, as I’ve mentioned, is a bird’s eye view of Dublin at 3:00 PM. But Joyce did this in another way, too, through a central concept called parallax. Merriam-Webster defines parallax as “the apparent displacement or the difference in apparent direction of an object as seen from two different points not on a straight line with the object” or “the angular difference in direction of a celestial body as measured from two points on the earth's orbit.” In Ulysses, Joyce employs it as a funny plot detail and at once as a deeply symbolic organizing principle. Before they ever meet, Bloom and Stephen are linked by their parallactic view of the same cloud. We don’t learn that the cloud Stephen sees in Part I of the novel is the same one Bloom sees in Part II until we see Bloom see it. We go back in time a bit to start Bloom’s story in Part II, and so we learn we are reading a story occurring simultaneous to one we’ve just read. (In this sense, readers actually do experience Ulysses partly through what Anderson refers to as “Messianic” time, where events and symbols prefigure and fulfill one another. But even still, Joyce is more interested in capturing a “clock and calendar” kind of experience.) Joyce capitulates the parallax motif when, in the final scene with Stephen and Bloom, he brings it back to its astronomic origins (it also happens to be one of my favorite quotes from the book):

“With what meditations did Bloom accompany his demonstration to his companion of various constellations?

Meditations of evolution increasingly vaster: of the moon invisible in incipient lunation, approaching perigee: of the infinite lattiginous scintillating uncondensed milky way, discernible by daylight by an observer placed at the lower end of a cylindrical vertical shaft 5000 ft deep sunk from the surface towards the centre of the earth: of Sirius (alpha in Canis Maior) 10 lightyears (57,000,000,000,000 miles) distant and in volume 900 times the dimension of our planet: of Arcturus: of the precession of equinoxes: of Orion with belt and sextuple sun theta and nebula in which 100 of our solar systems could be contained: of moribund and of nascent new stars such as Nova in 1901: of our system plunging towards the constellation of Hercules: of the parallax or parallactic drift of socalled fixed stars, in reality evermoving wanderers from immeasurably remote eons to infinitely remote futures in comparison with which the years, threescore and ten, of allotted human life formed a parenthesis of infinitesimal brevity.”

Stephen and Bloom—those two “evermoving wanderers from immeasurably remote eons”—are linked symbolically throughout the book, physically in their encounter in time and space, but also in their parallactic view of the same things, cosmic or otherwise. It’s this shared consumption that Anderson also suggests links us as a nation: “the second course of imagined linkage lies in the relationship between the newspaper, as a form of a book, and the market.” Newspaper’s ability to capture a simultaneity-along-time is how the technology teaches us to comprehend the complexities of disparate points of our world, but it’s our consumption of the stories that likewise link us. “Where were you during [moon landing, Berlin Wall falling, 9/11, January 6th, etc.]?” is a common question that helps us triangulate through parallax our relationship to each other as simultaneous experiencers of the same national and global histories.

There’s an important scene in Ulysses that helps elucidate what this all has to do with national belonging. In this scene, Bloom is being persecuted for being Jewish by some fellow men in a pub. The men heckle him as he stands up for himself, answering their bad faith questions thrown at him to stump and embarrass him. In his talk of persecution, the scene evokes similar questions Anderson raises.

“—Persecution, says [Bloom], all the history of the world is full of it. Perpetuating national hatred among nations.

—But do you know what a nation means? says John Wyse.

—Yes, says Bloom.

—What is it? says John Wyse.

—A nation? says Bloom. A nation is the same people living in the same place.

—By God, then, says Ned, laughing, if that’s so I’m a nation for I’m living in the same place for the past five years.

So of course everyone had the laugh at Bloom and says he, trying to muck out of it:

—Or also living in different places.”

Bloom’s definition—or definitions—of a nation have always intrigued me. I find his first definition endearing and true in a commonsensical way. It’s also really egalitarian, in the sense that national belonging only requires your presence (as opposed to legal, racial, or otherwise exclusionary criteria). But then his caveat—“or also living in different places”—also speaks to the complexity of nationality and nationalism. Whether closed or expansive, nationality/ism is a fraught topic in Ulysses (and in Ireland). Joyce’s novel seems to be interested in capturing Bloom’s first definition, and that’s where I see it so richly connecting to Anderson’s political theory. By setting the novel so concretely in one place at one time, our understanding of Irish nationhood and Irish people’s national belonging operates within Anderson’s “clock and calendar” model. Of course, Joyce was likely also sympathetic to Bloom’s second definition. As an expatriate (though Joyce preferred the term “exile”), Joyce couldn’t shake himself free of Ireland and its influence. To the question the hostile “citizen” character asks Bloom, Joyce might answer the same:

“—What is your nation if I may ask? says the citizen.

—Ireland, says Bloom. I was born here. Ireland.”

Newspapers have largely migrated to digital spaces, but they often keep their layouts. When we look at the homepage of a newspaper website, we still confront global simultaneities. The rest of our digital experience is certainly different. Social media, I’m largely thinking of, feels similar, though at once distinct just the same. I’m not a media theorist, so I’ll leave the theorizing to them, but I do think there’s a comparable parallel to our lives as the newspaper represented for Joyce—and later, radio (central to Finnegans Wake).

Back now to class, to what I said about a contemporary version of Ulysses, then. In Ulysses, the newspaper brings together the world itself and all its complexity before Bloom's very eyes. It's how he knows about the ship disaster in New York, the events of a war in Japan, and the market prices of goods and wares. It's also a place of advertisements, just like our internet. This is what makes Ulysses, despite its hyper-local nature, a global experience for Bloom and others. In that New Yorker piece, Rothman is right to point out that it’s a Dublin characterized by an over-saturation of media spectacle. Bloom may not have TikTok, but as he strolls (scrolls) through Dublin, he is assaulted with media imagery that defines his lived experience. Pre-internet was not a time of less media, just a different kind, which nevertheless bombarded populations often ill-prepared for the psychological and social changes it would bring. So, I take back what I said to my students in class. I think a Ulysses written today would not only have to confront how to incorporate the internet but would indeed benefit from reflecting on the complexity (for good or for ill) it adds to our lives. I’ll again leave it to media theorists to conceptualize what the internet has done to our conceptions of nationhood and national belonging, but if Joyce and Bloom’s visions of the nation were informed by newspapers, ours has to be, one way or another, informed by our new medias as well.